A young lady climbs out of a window dressed in men’s clothing with a pistol and her pet dog in hand. She meets another lady also dressed in men’s clothing and they ride into the night towards the coast with plans of their new life together abroad.

Hello and welcome to the seventh episode of Amorous Histories! I’m Annie Harrison, your resident history nerd for the next half an hour. Thank you to everyone who has supported me with social media follows, likes and shares, I’ve been feeling the love recently and I’m both surprised and grateful.

If you’re new hopefully you’ll like what you hear and help spread the word. And if you haven’t already found my social media pages I’m @AmorousHistories on Instagram and Facebook, and @AmorousHistPod on Twitter. You can find the transcripts and sources for each show on my website, with the fresh and very professional new url amoroushistories.co.uk. And if you like your podcasts available on YouTube I’ve started uploading episodes to my channel which is also, unsurprisingly, called Amorous Histories.

According to the internet reaching episode seven means I’ve beaten “podfade”, apparently seven is the magic number and if you make it this far you’ll probably keep going. So that’s good news. Seven doesn’t sound like much, but a lot of work goes into making an episode, whether it’s a history podcast like mine, or a comedy chat show, there’s a lot of stuff going on behind the scenes. Which is why it feels so sweet when you hit little milestones, I recently hit over 700 listens to the podcast and over 600 reads of my website so thank you!

Lesbians or not?

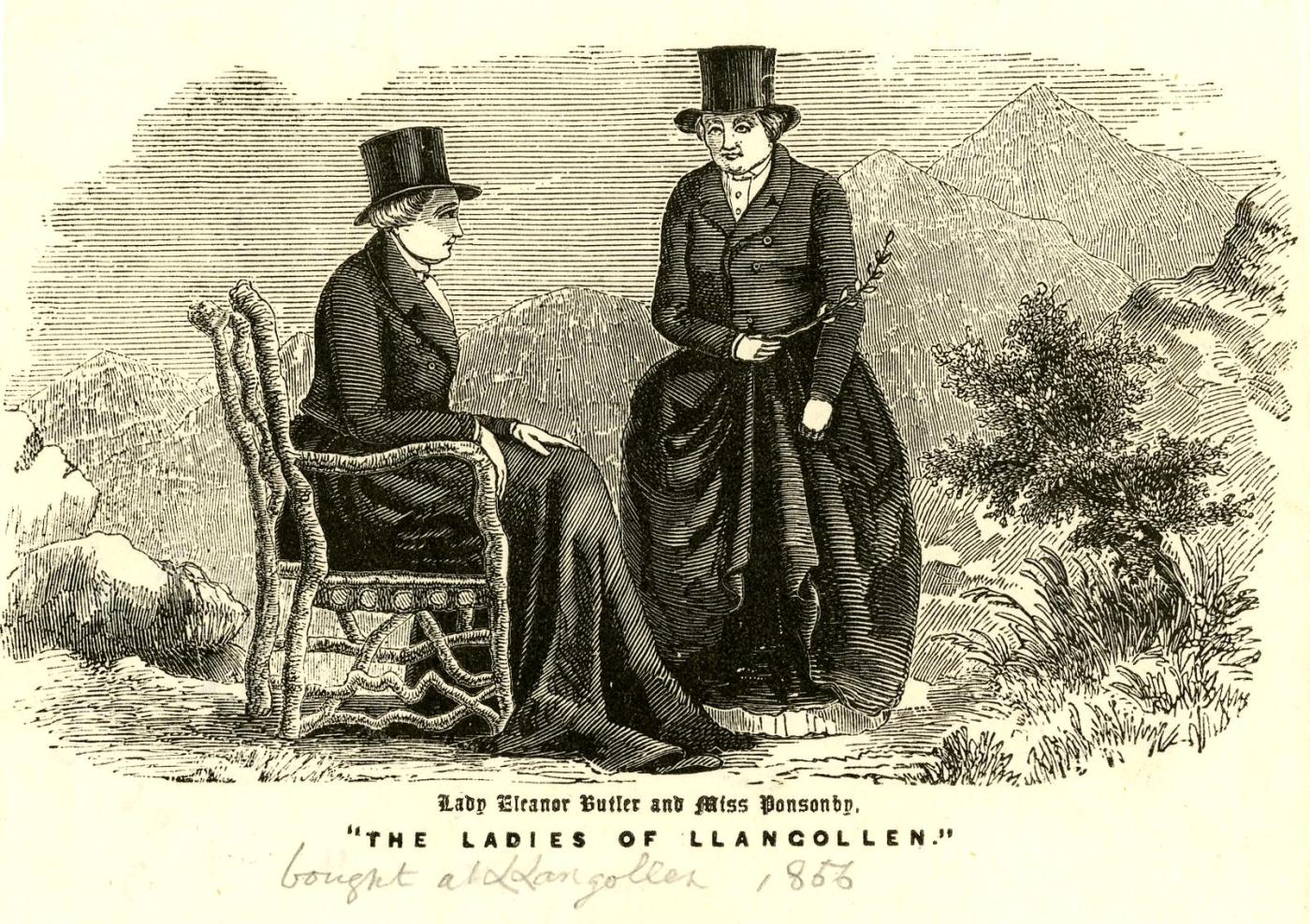

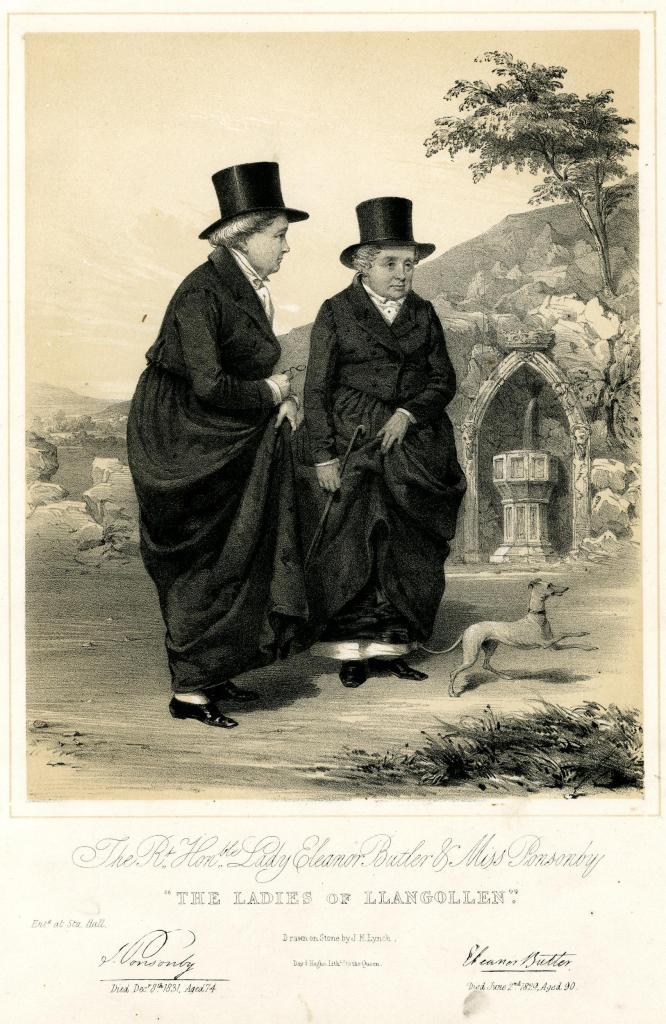

(c.1831-1865)

Today we’re going to be talking about the Ladies of Llangollen, an 18th century queer couple. I’ve had this on my episode list from the start, along with the story of Anne Lister. The TV series Gentleman Jack, which is based on Anne Lister, has just returned so I wanted to go gay for this episode but I knew if I did cover Anne Lister I’d probably get drowned out by everyone else doing the same. Sooo let’s supplement the discussion around Anne Lister and Ann Walker by meeting Sarah Ponsonby and Eleanor Butler.

But before we go any further I have to clarify some terms. The Ladies of Llangollen were not lesbians, because no one was a lesbian in the 18th century. You could be a lesbian if you were from the Greek Island of Lesbos, but that didn’t have anything to do with fancying women. So the historian in me can’t call them lesbians.

I could perhaps call them tommies, rubsters or flats, all of which were slang used in the 18th century or earlier to refer to women who were involved romantically or sexually with other women.

When talking about historical same-sex desire a lot of people seem to tend towards the word “queer”. We talk about queer history, queer literature, queer fashion etc. If gay/lesbian/trans is inappropriate because of the time period being discussed, then queer seems to be a good word to represent those in history who weren’t heterosexual, cisgender or people we would call quote unquote “heteronormative”. Although queer has it’s own complications and bagage, but that’s a whole other story. So today you will hear me refer to the ladies as quee because that is how I read their relationship

Context

In episode four we talked about molly culture and being a queer man in 18th Century London. Some of the people we learnt about were tried, imprisoned and executed for sodomy or their involvement with queer men. So was it the same for women who loved or slept with other women?

The short answer is no. In England it was not and never has been illegal for consenting women to have sex with women. And by consenting I also mean above the legal age of consent. On his website Rictor Norton writes “There have been no laws against lesbians in England and America”, he goes on to quote Louis Crompton who said:

“In Europe before the French revolution, however, notably in such countries as France, Spain, Italy, Germany, and Switzerland, lesbian acts were regarded as legally equivalent to acts of male sodomy and were, like them, punishable by the death penalty. On occasions, executions of women were carried out”.

But Norton notes that “such instances were rare, and laws which formally existed on the statute books were seldom enforced in practice.” The Ladies of Llangollen were subject to English law as they lived in Wales so they didn’t have to hide their relationship like queer men did.

Ireland

The story of the Ladies of Llangollen begins in Ireland. Lady Eleanor Charlotte Butler, the older of the two by 16 years, was born in 1739. She was a member of the Butler family, the Earls of Ormonde, as the daughter of Walter Butler, the 16th Earl of Ormonde and Eleanor Morres. The family’s seat was Kilkenny Castle, in County Kilkenny, south-east Ireland. She was educated at a convent in France. Sarah Ponsonby was born in 1755, the daughter of Chambré Brabazon Ponsonby and Louisa Lyons. Sarah was orphaned as a child and lived with her relatives, Sir William and Lady Betty Fownes, in Woodstock, County Kilkenny. Sir William and Lady Betty decided to educate Sarah at Parks boarding school in Kilkenny, which is where she would have met Eleanor. Lori Moriarty notes in her talk The Lives and Afterlives of the Ladies of Llangollen that when they met Sarah would have been 13 and Eleanor would have been 29.

Their friendship continued for ten years before they first attempted to leave Ireland for England, when Sarah was 23 and Eleanor was 39, with neither of them married. On the night of Monday 30th March, 1778, Sarah – dressed in men’s clothing, carrying a pistol and her dog Frisk – snuck out of a window at Woodstock and met Eleanor who had ridden 15 miles from Kilkenny Castle also dressed in men’s clothing. The pair then made their way 23 miles to Waterford where they had planned to catch a boat to England. Unfortunately, despite their apparent planning, they missed the boat and had to spend the night in a barn. By the time the morning had come around their families had found them and taken them home, Sarah with a serious fever.

Both families were upset and shocked by the women’s attempt to travel to England. In a letter to a family friend, Mrs Goddard, Sarah’s relative Lady Betty writes that “there was no man concerned with either of them” meaning that they weren’t running off to be with men, which was of great relief to both families. Sarah had revelved that her and Eleanor had long been planning to travel to England and live together, which sound pretty frickin queer to me.

You may be wondering why, if this is all so respectable and platonic then why did they scheme and hide their move to England? Well Sarah was 23 so she was ripe to be married off to a suitable wealthy man, but it transpires that her guardian, Sir William had actually proposed marriage to her, even though his wife Lady Betty was still alive. From Sarah’s letter historians learnt that Sir William had said to Sarah that once Lady Betty was dead, he planned on marrying her. Which is just a horrific proposal, I mean Lady Betty is still alive and well for one thing, let alone the fact that he’s old and was charged with her care when she became an orphan, aged eight I think she was! So yeah, that’s what Sarah was running from. As for Eleanor, she sort of had the opposite problem. She was 39 and unmarried, her family were about to pack her off to the convent in France where she was educated to become a nun. Despite the fun a queer woman could have in a nunnery Eleanor clearly didn’t like the sound of that plan. Perhaps she’d already found the person she wanted to spend the rest of her life with in Sarah?

After the escape attempt the two families prevented the women from seeing each other. Sarah’s family thought that Eleanor was leading her astray, and Mrs Goddard, the family friend mentioned earlier, visited Sarah to try and dissuade her from attempting to travel to England again, telling her that Eleanor had quote “a debauched mind”. That sound like code for queer to me.

About three weeks after their failed escape Eleanor manages to break out of the property where her family were keeping her, which was Borris House about 12 miles from Woodstock, where she travelled to and hid in Sarah’s room for two days with the help of a domestic servant, Mary Caryll I need a gay alarm or something because come on.

Eventually, for reasons that don’t appear to be clear, both families stop fighting against the women’s wishes and agreed to allow them to move to England together, and to pay them an allowance on which to live. In May 1778, just two months after the women had snuck out of their homes, Sarah and Eleanor were on their way to England to start their new life together, along with the servant who helped them, Mary Carryll.

New Beginnings

The two women travelled around Wales and part of England on a sort of mini tour before settling in Llangollen, leasing a cottage in 1780. We know about this time of their lives from sources such as Sarah’s journal which she entitled “Account of A Journey in Wales; Perform’d in May 1778 By Two Fugitive Ladies And Dedicated to her most tenderly Beloved Companion By The Author”. I feel like Sarah is being a little bit tongue in cheek there referring to herself and Eleanor as fugitives. Did she feel like they were fleeing persecution or judgement perhaps? Or that their behaviour could be seen as criminal? Also I’d love to see a compare and contrast of Sarah’s and Eleanor’s diaries and letters with Anne Lister’s to see if you could read any queer language or coding used by both parties. And by queer coding, I don’t mean how Lister wrote in code, but did they for example, have words with double meanings that were known only to the queer community? Someone must have written something on that? If you’re shouting at me right now because you know of a piece of work that does that then please let me know! I’m not affiliated to a university or institution so I’ve not got access to the articles kept behind paywalls.If I miss something it’s not for want of trying, it’s just capitalism doesn’t swing in my favour. It’s at this point that I should probably plug that I set up a Buy Me a Coffee account, buymeacoffee.com/amoroushistpod so that I could fund the research for this podcast. Because currently all my money goes our gas and electricity supplier…

Llangollen

Anyway Sarah and Eleanor have now settled in Llangollen, they’ve got their little cottage, Plas Newydd, and they’re living out their dreams. Hold your horses because it’s about to get really gay (again). They spent their time renovating the cottage into a gothic style, they improved their gardens, curated a library, eventually they created a 9 acre farm with four cows, and apparently – don’t quote me on this – they had a dog or a succession of dogs named Sappho. Now if that doesn’t sound like the ultimate lesbian cottagecore fantasy then I don’t know what does. It is important to note that Eleanor and Sarah were both educated, upper-class women from wealthy families with titles and land, so the way in which their situation plays out is really aided by the fact that they have so much privilege on their side, especially compared to the mollies and queer men we spoke about in episode four.

The ladies had wanted to live in “seclusion” however the novelty of their living situation made them somewhat of a tourist attraction. Patricia Hampl wrote quote::

During the Ladies’ long years in their home, […] it seems just about everyone beat a path to the heavily ornamented Gothic door of their remote “Cottage.” Wordsworth and Southey composed poems under its low roof; both Shelley and Byron turned up to talk and “stare,” apparently flummoxed by the orderly cloister life of the Ladies. Charles Darwin came as a child in the company of his father; Lady Caroline Lamb (the novelist and lover of Lord Byron — and a distant relative of Sarah) made a visit. As did Sir Walter Scott. Even the Duke of Wellington (a treasured friend) and De Quincey (“coldly received”) — on and on the personages of the age made pilgrimage to the isolated Welsh village on the river Dee. Josiah Wedgwood visited the Ladies to tour and opine about the rock formations of the surrounding “savage” landscape.

The poet Anna Seward, […] visited and corresponded with the Ladies. Various royals from the Continent also made the pilgrimage — the aunt of Louis XVI, Prince Esterházy from Budapest. Coming and going, the aristocrats paid wistful (or baffled) homage to a way of life rare in its independence and chosen affection. End quote.

Unsurprisingly queer women such as Anna Seward, Anne Lister and her lover Mariana Belcombe, gravitated towards the Ladies. They inspired some of Seward’s writings, most notably the poem Llangollen Vale, and Anne and Mariana spent time trying to figure out if Sarah and Eleanor were in a romantic relationship. In one letter to Anne, Mariana asked: “Tell me if you think their regard has always been platonic & if you ever believed pure friendship could be so exalted. If you do, I shall think there are brighter amongst mortals than I ever believed there were..” Anne replied saying: “I cannot help thinking that surely it was not platonic. Heaven forgive me, but I look within myself & doubt. I feel the infirmity of our nature & hesitate to pronounce such attachments uncemented by something more tender still than friendship.” So they got Anne Lister’s gaydar pinging. It’s thought that Anne Lister’s visit to the Ladies in July 1822 further proved to her that women could live together as lovers.

It wasn’t only queer women who suspected the ladies relationship wasn’t purely platonic. In July 1790 three London newspapers speculated on their living situation. In the St James’s Chronicle an article titled “Extraordinary Female Affection” was published. The opening paragraph wasn’t messing around saying, quote:

“MISS Butler and Miss Ponsonby, now retired from the society of men, into the wilds of a certain Welch vale, bear a strange antipathy to the male sex, whom they take every opportunity of avoiding.”

The article goes onto to describe the ladies, quote:

“Miss Butler is tall and masculine. She wears always a riding-habit. Hangs up her hat with the air of a sportsman in the hall; and appears in all respects as a young man, if we except the petticoat, which she still retains. Miss Ponsonby, on the contrary, is polite and effeminate, fair and beautiful. […] Miss Ponsonby does the duties and honours of the house; while Miss Butler superintends the gardens and the rest of the grounds.”

This was clearly an attempt to force the women into heteronormative roles of husband and wife – which still happens to queer couples today by the way. They’ve decided to characterise Eleanor as the man, wearing a riding-habit and doing the gardening, whilst Sarah is the woman managing the house, and the description of her as “effeminate, fair and beautiful” conjure stereotypical images of late eighteenth century woman in a dress. We know this is not true though. From the accounts we have of them we know that both Eleanor and Sarah favoured riding habits. In her diary Anne Lister wrote of Sarah, quote:

“A large woman so as to waddle in walking but, tho’, not taller than myself. In a blue, shortish waisted cloth habit, the jacket unbuttoned shewing a plain plaited frilled habit shirt – a thick white cravat, rather loosely put on – hair powdered, parted, I think, down the middle in front, cut a moderate length all round & hanging straight, tolerably thick. The remains of a very fine face. Coarsish white cotton stockings. Ladies slipper shoes cut low down, the foot hanging a little over. Altogether a very odd figure…Mild & gentle, certainly not masculine & yet there was a je-ne-sais-quoi striking.”

by Richard James Lane, printed by Jérémie Graf, after Lady Mary Leighton (née Parker), 1836

I can’t help but hear that in Surane Jones’ voice from Gentleman Jack, haha! The few contemporary images we have of them also represent them in what has been variously described as “conservative” dress. There’s a 1828 sketch by Mary Parker, that I’ll share on my social media, of the ladies in their library, and strangely Eleanor is shown wearing the order of Saint Louis, a French order of chivalry awarded to exceptional officers. There’s plenty more that can be said about their fashion choices but sadly I don’t have time to squeeze it in!

As well as misrepresenting their dress the St James’s Chronicle article also divides their domestic roles. We know that they shared responsibilities gardening and managing the household together, along with help from their servant Mary. Improving Plas Newyyd was their joint project.

The “Extraordinary Female Affection” article was reproduced – slightly edited – in the General Evening Post and the London Chronicle a fews days after the original was published. Sarah and Eleanor didn’t take kindly to this report and they wrote to Edmund Burke enquiring what legal action could be pursued, and he tells them just ignore the newspapers, quote “the rest of the world will not be in the smallest degree influenced by it”. Which we all know isn’t true.

Ends

There’s so much to talk about when it comes to the Ladies of Llangollen. I quickly want to touch on their belongings. The books in their library were embossed with their initials EB on the front, SP on the back [insert gay alert]. The British Museum holds a pair of chocolate-cups, covers and saucers owned by the ladies. The chocolate-cups have a view of Plas Newyyd on one side and the arms of the Butler and Ponsonby families on the other, and each saucer is monogrammed. [Insert gay alarm].

After over 50 years together Eleanor passed away in 1829 and Sarah soon followed in 1831. They never returned to Ireland. They were buried together with Mary Carryl who had died in 1810. A three sided gothic monument marks the women’s final resting place in St Collen’s churchyard, Llangollen, Wales.

Now I really have run out of time. There is so much I haven’t talked about including Mary Carryyl, the women’s own writing, architecture, politics and the good old fashioned “they were just good friends” debate… This is just supposed to be an informed and interesting overview of the ladies lives, and if you want to learn more I fully encourage you to do so. I’m going to leave you with Eleanor’s diary entry from Thursday 22nd September 1785:

“Up at Seven. Dark Morning, all the Mountains enveloped in mist. Thick Rain. A fire in the Library, delightfully comfortable, Breakfasted at half past Eight. From nine ’till one writing. My Beloved drawing Pembroke Castle – from one to three read to her – after dinner Went hastily around the gardens. Rain’d without interruption the entire day – from Four ’till Ten reading to my Sally – She drawing – from ten ’till Eleven Sat over the Fire Conversing with My beloved. A Silent, happy Day.”

I hope you enjoyed spending time with the Ladies of Llangollen, if you’re interested in finding out more I really recommend Lori Moriarty’s talk on their lives and afterlives, a link to that video will be on my website.

If you liked this episode please leave Amorous Histories a little review or some stars on your podcast app or website! You should be able to find me wherever you get your podcasts, even YouTube. You can also follow my socials @AmorousHistories on Instagram and Facebook, and @AmorousHistPod on Twitter. Transcripts and sources are at amoroushistories.co.uk. Please feel free to DM or email me amoroushistories@gmail.com if you have any questions, episode suggestions or want to collab.

Stay sexy!

Sources

The Ladies of Llangollen, Wellcome Collection, Sarah Bentley https://wellcomecollection.org/articles/WqewRSUAAB8sVaKN

Lesbianism and the criminal law of England and Wales, Caroline Derry, https://www.open.edu/openlearn/society-politics-law/law/lesbianism-and-the-criminal-law-england-and-wales

The Nature of Lesbian History, Rictor Norton http://rictornorton.co.uk/lesbians.htm

Case study: terms for lesbian(ism), Examining the OED, Charlotte Brewer

The Myth of Lesbian Impunity Capital Laws from 1270 to 1791, Louis Crompton, Journal of Homosexuality. Vol. 6(1/2), Fall/Winter 1980/81 https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishfacpubs/59

The Ladies who were famous for wanting to be left alone, excerpt adapted from The Art of the Wasted Day, Patricia Hamp, 2018 https://longreads.com/2018/04/17/the-ladies-who-were-famous-for-wanting-to-be-left-alone/

The Lives and Afterlives of the Ladies of Llangollen, Lori Moriarty https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GMEiZKFESNg

“Extraordinary Female Affection”: The Ladies of Llangollen and the Endurance of Queer Community, Fiona Brideoake, Queer Romanticism https://www.erudit.org/fr/revues/ron/2004-n36-37-ron947/011141ar/

The Ladies of Llangollen, British Museum https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/desire-love-and-identity/ladies-llangollen

Lesbian love and coded diaries: the remarkable story of Anne Lister, Lydia Figes https://artuk.org/discover/stories/lesbian-love-and-coded-diaries-the-remarkable-story-of-anne-lister

The Ladies of Llangollen, Kelly M. McDonald, https://ladiesofllangollen.wordpress.com/